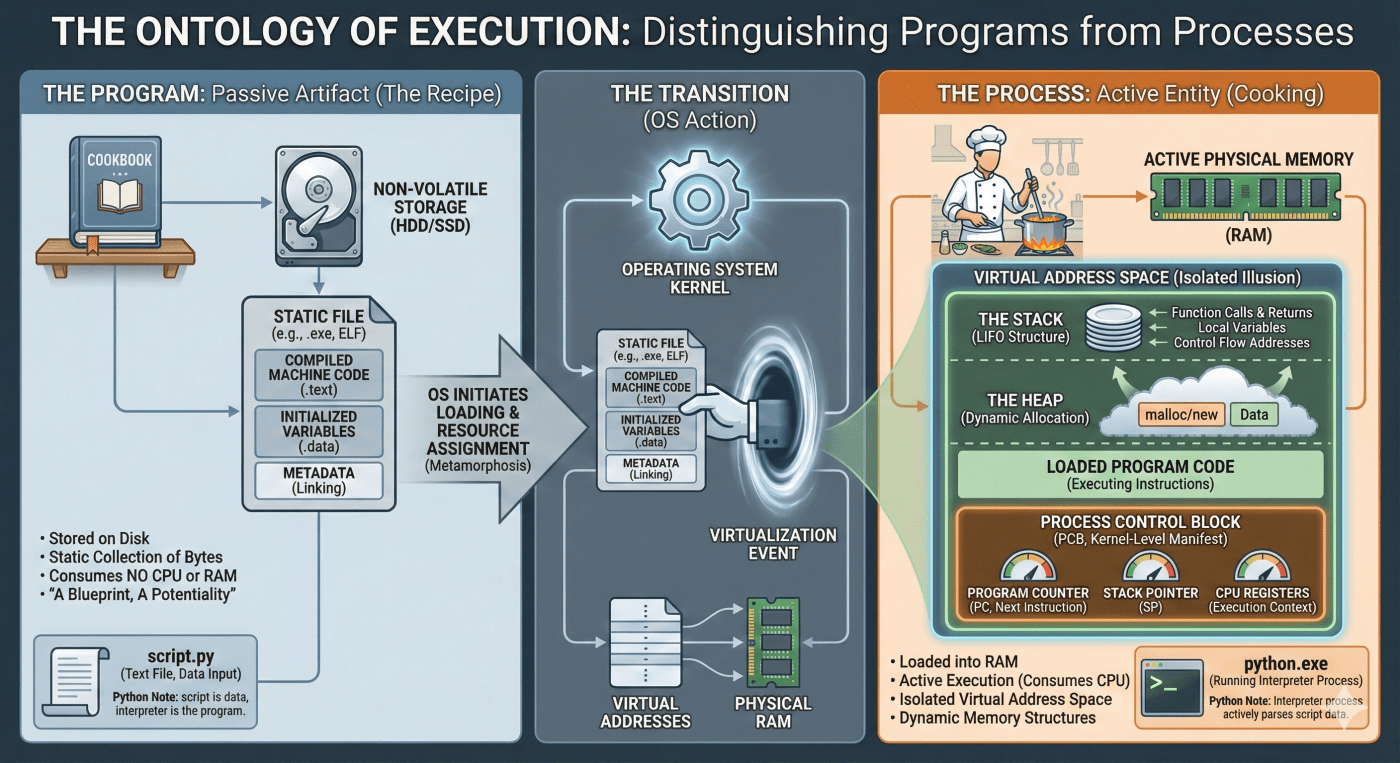

A Program is Not a Process In the world of computing, we often use the terms “program” and “process” interchangeably, but they represent two fundamentally different states of existence. Think of a program like a recipe in a cookbook: it is a static set of instructions sitting passively on your hard drive. It consumes no computing power and has no “life.” A process, however, is the act of cooking that recipe. It is a dynamic, active entity that the operating system loads into memory. When you double-click an icon, the OS transforms the passive program into an active process by assigning it resources like RAM, a program counter, and CPU registers. This distinction is crucial for developers, especially in interpreted languages like Python. When you run a Python script, the “process” isn’t actually your script—it’s the Python interpreter. Your script is merely the data that the interpreter reads to decide what to do next. Understanding this separation helps us debug smarter and understand how our code actually lives inside the machine.

Technical Analysis: The Static vs. Dynamic Duality

The distinction between a program and a process forms the bedrock of operating system theory. The confusion between the two often stems from the user interface level, where clicking a program icon seemingly “starts” it. However, beneath the graphical abstraction, a complex metamorphosis occurs, transforming a passive storage artifact into an active system entity.

The Passive Artifact: The Program

A program is, in its essence, a file stored on a non-volatile medium such as a hard disk or solid-state drive. It is a static collection of bytes organized according to a specific executable file format, such as the Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) on Linux or the Portable Executable (PE) format on Windows. This file contains the compiled machine code (the .text section), initialized variables (the .data section), and metadata regarding dynamic linking and relocation.

Crucially, a program is inert. It consumes zero CPU cycles and requires no active physical memory (RAM) allocation beyond what the filesystem cache might speculatively hold. It is a blueprint, a potentiality rather than an actuality. In the context of interpreted languages like Python, this distinction is even more pronounced. The Python source code file (script.py) is technically not the program being executed by the hardware. It is a text file serving as input data. The actual “program” in the strict architectural sense is the Python Interpreter binary (python.exe or /usr/bin/python). When a user initiates a script, the operating system loads the interpreter’s machine code into memory. This interpreter then parses the script file, translating its high-level logic into bytecode or machine instructions in real-time.

The Active Entity: The Process

A process is the instantiation of a program. It is the “spirit” breathed into the static “body” of the code. When the operating system creates a process, it allocates a distinct Virtual Address Space to it, creating an illusion of isolation where the process believes it owns the entire memory range of the machine.

This active state requires the initialization of several dynamic memory structures that do not exist in the static program file:

The Stack: A LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) structure used for managing function calls, local variables, and control flow return addresses. The stack grows and shrinks dynamically as functions are invoked and return.

The Heap: A region of memory used for dynamic allocation (via malloc or new) where data with an unpredictable lifetime is stored. Unlike the stack, the heap is managed explicitly by the programmer or a garbage collector.

The Process Control Block (PCB): A kernel-level data structure that serves as the “manifest” for the process. It tracks the Program Counter (PC), which points to the next instruction to execute, the Stack Pointer (SP), and the CPU registers containing the current execution context.

The transition from program to process is not merely a copy operation but a virtualization event. The Operating System (OS) sets up page tables to map virtual addresses to physical RAM, ensuring that the process cannot access memory belonging to other processes or the kernel. This isolation is what allows modern systems to be robust; if a process crashes, the program file remains intact on the disk, and other processes remain unaffected.

Leave a comment